Dominika Micał: You’re working now on Die schöne Müllerin with Barokksolistene but your relationship with Franz Schubert has lasted much longer. How did your attachment to his songs start?

Thomas Guthrie: We’re doing three works for their 200th anniversary: Die schöne Müllerin will be released this year [You can listen to Der Müller und der Bach here and Des Baches Wiegenlied here – DM.], Winterreise in 2027, and Schwannengesang in 2028. I fell in love with Schubert’s songs before my voice broke. I even recorded some as a choirboy. I sang my first Winterreise in 1991. I loved the traditional way of performing it, for instance, Gérard Souzay’s, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s or Fritz Wunderlich’s recordings. I grew up with this tradition.

Then why do you perform it with an early music ensemble?

I did my PhD with Peter Seymour, who was a great lover of this repertoire and also an early music specialist. He opened my eyes to the idea that the early music principles applied right into the early 19th century and that the tradition of rhetoric (how you perform and how you write the speech) was so strong. It’s no coincidence that the early music composers wrote very little in the way of instructions, tempo or dynamics. Even Schubert doesn’t give you very much. And suddenly in the 1840’s it changed – because the relationship between the composer and the performer changed. Schubert was still closer to that earlier style. He understood that singers would ornament, that they would take what he’d written and then make it work in whatever situation they were, to communicate the text. And we know he played the guitar himself, and that the instruments that they were using, there were nothing like the big Steinway grand pianos that we have. And also the situation of music-making was very different – they sang in his front room, with a drink and with friends. So when I started to work with Barokksolistene on The Alehouse Sessions project, we wanted to revive that practice. We wanted it to be as Schubert intended it – to really make a room feel alive with the music. It was about this intimate, warm, human connection.

When in 2014 I staged the Bach motets and found out that those motets were written for funerals, I thought we could do an evening focused on the contemplation of mortality. We started Death Actually with Die schöne Müllerin – a moving, tragic story about death, shown with a puppet – and then it moved to the funeral, and the wake, the celebration at the end of the evening. On that occasion, I arranged Schubert for Barokksolistene.

Where did the idea of presenting songs or motets in theatrical form come from?

I’m always interested in all forms of storytelling. I feel very fortunate to work in theatre and music; I see them both as ways of telling stories. I think Schubert was interested in that too. I think his Liederabends served the same ends that storytelling does: bringing people together, giving a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, and fun, and education in some ways. So, I don’t see my projects as making Schubert theatrical, I see it as, in a sense, ornamenting. Puppets, for instance, are wonderful. In 2004, I just worked with puppets a little bit, I was excited by them because of the way they inspire the imagination because they are not specific. We then had the opportunity to do Winterreise in a beautiful old theatre in Kent. I had seen some stage productions of that cycle but I found them problematic. There was one with Simon Keenlyside – impressively danced, very beautifully sung, focused on the character and the physicality. But the piano was offstage in the wings. It reminded me of Deborah Warner’s production of the St John Passion I saw at the English National Opera with the orchestra in the pit. In both projects, the visual and the audible were separated in a similar way. It was never going to work in a fully satisfying way because for Bach and Schubert the music carries the storytelling. So we wanted to do with Winterreise something which would excite people visually and inspire their imagination, but also keep the music-making right at the centre. And that’s when the puppet seemed to be the perfect thing. We can light it in a magical way but we never go away from the piano. It is right there. The puppet just becomes his character. Therefore, we could, in a way, challenge the current tradition of Schubert, which feels like it’s become less and less authentic, less and less truthful to what Schubert was doing. And at the same time, we can excite an audience. I don’t want to say that tradition doesn’t have value, that those things are bad or that they can’t be moving. But we should challenge it to find the heart of what makes these great, wonderful, musical stories work and live.

Is telling new stories based on old music a way to make it alive for us?

I try not to impose anything on the music. One of the very first productions I did of my own was Purcell’s Fairy Queen. And that was the most imposing I feel I’ve ever been. We set it in a Victorian mental hospital. We were inspired by the Victorian painter, Richard Dadd, who ended up in an asylum. He was obsessed with A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He painted incredibly detailed works on subjects taken from it. Of course, Fairy Queen is a fantasy on A Midsummer Night’s Dream, rather like these paintings. They were a framework where the music could work in a way that served the music. We had to make sure the music was never put to any other purpose than that for which it had been intended. So I would say even when my work has taken me into those areas where it feels like we’ve gone somewhere else, I feel that the only justification for doing so is to find ways to unleash what’s already there. I find it problematic when people impose separate concepts on the music. And the audience often finds it difficult to understand such projects either.

Do you think storytelling can help us restore the community? In a world dominated by new technology, we seem to go rather towards alienation, closing ourselves in our heads.

That’s the centre of my mission as an artist. I felt this very strongly in the pandemic that venues are, by and large, unhelpful. Let’s take Shakespeare’s The Globe – it’s built up high, and everyone is close enough to throw something at the performers if they don’t like the show. It’s not about big sets or big expenses or technology. It’s exactly the opposite – the most important thing is human contact. And then there are those hierarchical later theatres, which shaped our musical practice. That’s why we have song recitals with a very famous singer with a white tie and a big piano, in a refined venue. This is not what Schubert was doing. With Music and Theatre for All, we initiated The Hive project which encompasses exactly what we are talking about. Our project is to challenge the way spaces are designed and propose other possibilities, closer to the idea of The Globe. We cannot only think about large venues like Carnegie Hall or Royal Opera House, as wonderful as those institutions and buildings are at trying to welcome people in. The red velvet, the gold and the boxes are not about storytelling anymore.

How about new technologies?

Technology fascinates me. But I worry about amplification. It’s becoming so prevalent, and I think it brings with it a sense of authority. I was in Esbjerg once. On one of the squares, there was a children’s event. And in one corner, there was a storytelling tent with a few children sitting on straw bales. In front of them, very close, two storytellers, actor-type characters. They were very close to the children but they had microphones and behind them was a bank of speakers. The children were overwhelmed. Sometimes we cannot tell who is speaking on the stage because it is all indirect and very loud. I feel disheartened by it and I want to challenge it. That is why I like to work in smaller venues. We have to value being in the same space with someone and having a natural energy exchange, not coming through a speaker.

Do you think that despite all of that there is still a place for magnificent, immersive spectacles, even though we do not feel a connection with the rest of the audience?

Yes, I do. I think that it does work. And I feel that’s why I want to be cautious, to say there’s not only one way to do it. Some pieces, Aida for instance, rely on a certain amount of spectacle. The right production and the right approach can absolutely give you that feeling of being alone and connected to, spoken to and involved personally in any space. I do think virtual reality can work as well. It can affect you, and that’s the only thing that matters. Are we really affecting people as storytellers? I love the idea that there are millions of ways of doing it because that’s the way it should be. I believe that some principles have to be at the heart of anything that’s truly of quality. And it goes back to the Bach and the Schubert – let’s be open, let’s be imaginative, but let’s remind ourselves always of how pieces work and what is their value.

You work a lot with non-professionals. How do you combine the pursuit of quality with working with amateurs?

I think it just comes down to the attitude that we’re after interesting quality and we’re interested in authentic human connection. There’s no dumbing down required when you when you’re doing that. Of course, we can simplify things – we would not do the whole Die schöne Müllerin to a group of six-year-olds. But we can do one or two songs, with the right approach, and get them involved. We have to also remember that Schubert wasn’t writing for an elite audience only. He was writing for his friends, of course, educated to a certain degree. But the reason they loved his music was because of this common humanity. Schubert was a human being, not only a great composer. He was drinking and swearing, and having relationships. We have this idea of historically- informed performance practice (which can be problematic), and now we have to go back to really find the human spirit in music, that is our job. And we have to translate or deliver it now, in this moment, in this climate, in this room, taking into consideration the way I’m feeling today, and the way that other people may be feeling…

So, are The Alehouse Sessions and The Playhouse Sessions the retelling of the core of that story and that music and not about the details of the performance practice?

Yes, because I think how they played trills is outside the core. I think it’s interesting and worth studying – it can lead us to things which inform how we understand the core. But that’s not the core. The core is having a good time.

You do mostly early music and 19th-century music. Do you think that 20th-century composers contributed to the abandonment of storytelling?

I think it goes back to before the 20th century. I think that started in the 19th century when rhetoric stopped being taught in universities, in 1840. To put it simply, the Romantic period contributed to the development of the cult of the individual to a certain extent. So suddenly you have Mahler in the woods, writing music which is not about the audience. It’s about him. That’s not to say he was not a genius artist. But I think there’s a problem starting there that later deepened. Over time, the bond was broken, and the basic principle of storytelling – addressing the audience – was broken. But the human relationship to melody and harmony has not changed. A beautiful tune and a beautiful harmony move us. There is, of course, wonderful 20th– and 21st-century music which incorporates these things. It’s not lost. And there is a lot of fantastic popular music and there are some wonderful musicals… There’s so much hope for this human level of musical communication. But we have to go back to finding what moves people. And if that’s melody and harmony then I don’t think that’s going to limit us. There will always be stories to tell and there will always be more ways to tell them.

The interview was first published in Polish in Ruch Muzyczny 2023, No. 20.

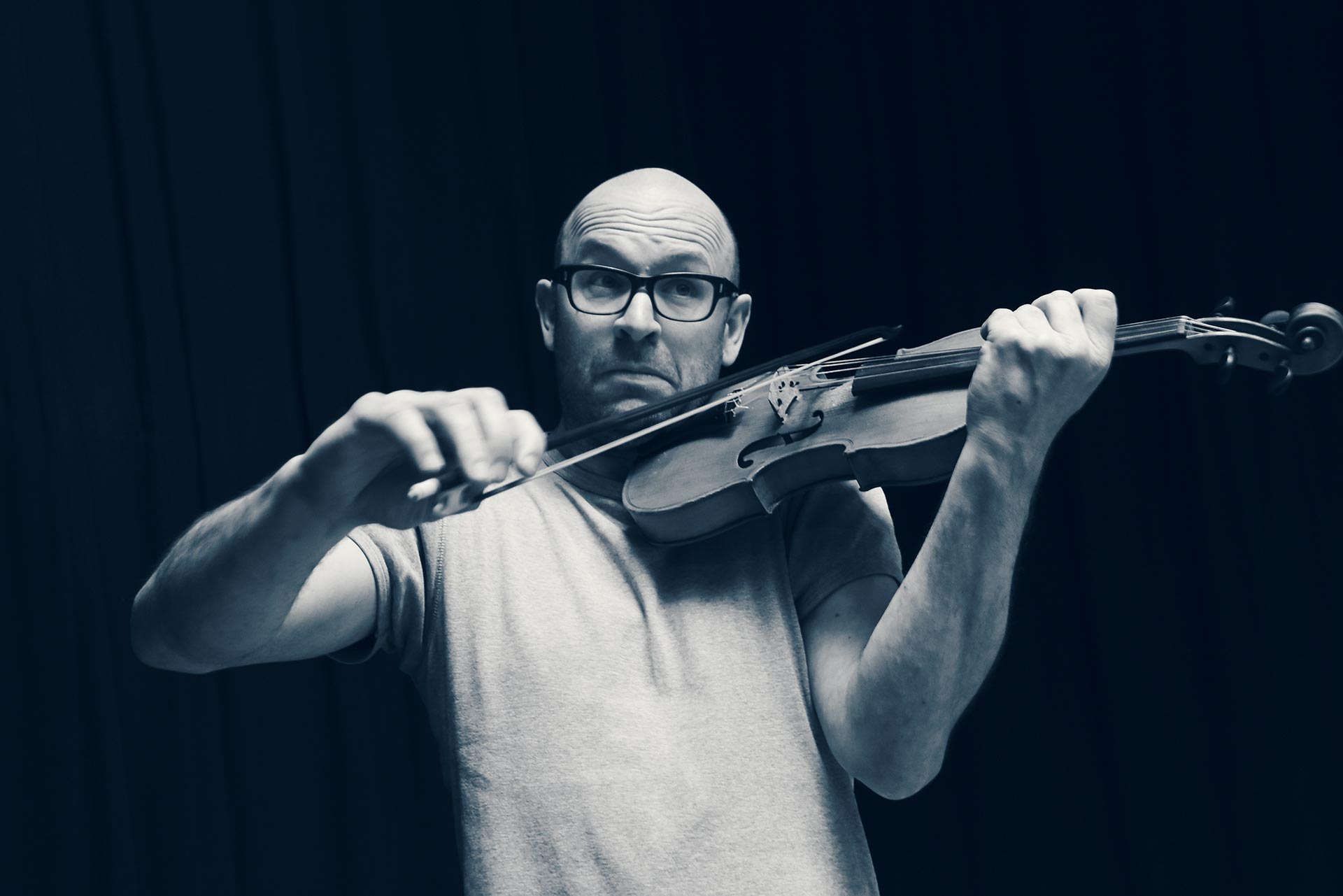

Photo of Thomas Guthrie by Gorm Valentin, for Barokksolistene’s The Alehouse Sessions project.